PART 1: Progress, Targets and Drivers

Part 1 sets out the Panel’s view on the progress towards and likelihood of reaching Scotland’s fuel poverty targets, how the Strategy is supporting this and the extent to which the four drivers of fuel poverty are being addressed. We begin with our assessment of progress on the fuel poverty targets before setting out our analysis on the framing of the Strategy and its impact on the periodic reporting. We then review each fuel poverty driver in turn in relation to the evidence given in the Scottish Government’s Periodic Report.

The Fuel Poverty Targets

The ambition of Scotland’s fuel poverty targets and its robust definition of fuel poverty demonstrate laudable national commitment. Scotland’s other statutory targets also help to set the tone for a strategic direction which has the potential to reinforce the work to tackle fuel poverty, namely the child poverty, climate change and heat network targets.

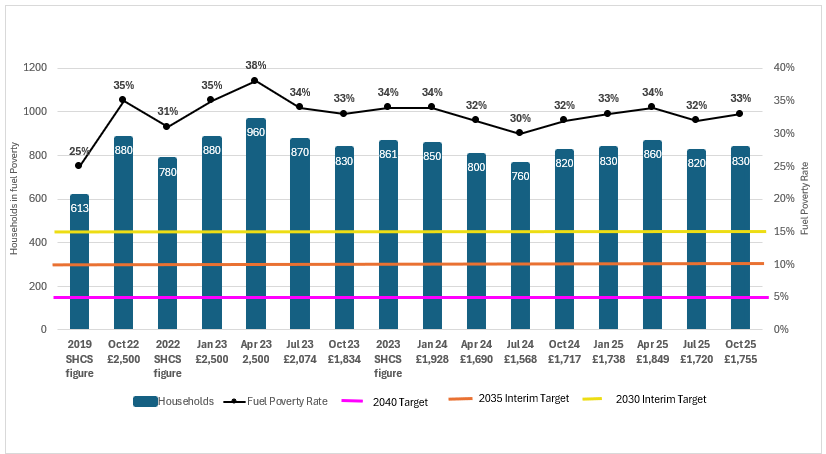

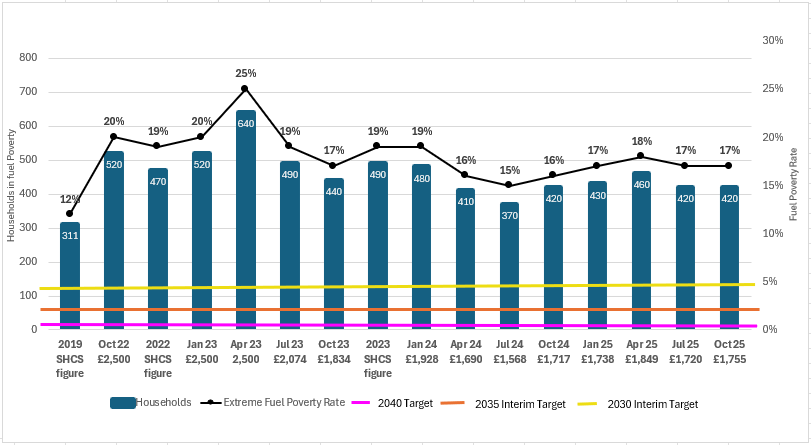

Figures 1 and 2 show levels of fuel poverty and extreme fuel poverty from 2019 to July 2025, compared to the statutory targets. The first interim target sets out that by 2030, no more than 15% of households in Scotland are in fuel poverty, no more than 5% of households in Scotland are in extreme fuel poverty, and the median fuel poverty gap is no more than £350. However, the latest statistics suggest rates far in excess of this (34%) and significantly increased from the recorded level of fuel poverty in 2019. When the fuel poverty targets were set, fuel poverty rates stood at 25%. Implicit in the target milestones is achieving an annual average 1%+ reduction in fuel poverty levels sustained over a 20-year period.

Figure 1: fuel poverty time series 2019 to October 2025, with statutory targets (source: Scottish House Condition Surveys 2019, 2022, 2023 and Scottish Government quarterly modelling based on the quarterly energy price cap)

Figure 2: extreme fuel poverty time series 2019 to October 2025, with statutory targets (source: Scottish House Condition Surveys 2019, 2022, 2023 and Scottish Government quarterly modelling based on the quarterly energy price cap)

The Panel considers that in setting ambitious interim targets and a target for 2040, the Scottish Government did not set out a clear vision for progress – or monitoring and evaluating thereof – in improving energy efficiency, increasing income levels or assumptions on energy mix and costs. There is little evidence in the Periodic Report to suggest that the current Strategy is meeting or can meet these statutory targets. The Periodic Report does not contain any self-reflection on how far the Scottish Government’s policy actions between 2021 and 2024 have taken it towards meeting the 2030 interim target date. It also does not contain any assessment of what additional measures are needed (if any) to achieve either the interim or the 2040 targets.

Based on the best available evidence, the Panel’s view is that given current levels of fuel poverty, the 2030 interim fuel poverty targets[7] are extremely unlikely to be met. The Panel is also of the view that meeting the 2040 target, although still in sight, will be a challenge requiring a new strategic approach and greater strategic prioritisation.

We would note, too, that if the Scottish Government is unable to make an assessment of progress, other stakeholders will also be unable to do so, including key delivery partners. This will limit the capacity for pro-active actions where needed and risks creating uncertainty around the commitment of the Scottish Government to the statutory targets.

In Part 3 of our response, we recommend that the Scottish Government should be transparent in its assessment of whether the targets are achievable.

The Fuel Poverty Strategy

The Strategy was published before the appointment of the Statutory Panel. We acknowledge that the Scottish Government consulted key stakeholders in its development. In previous advice to the Scottish Government between 2022 and 2024, the Panel identified weaknesses in the Strategy and explained that as it was developed in response to the prevailing circumstances at the time, it did not respond to the challenges that were now presenting in Scotland. The Panel also highlighted that the wider policy landscape was evolving, and that some of the actions in the Strategy did not address fuel poverty specifically.

It is the Panel’s view that the Scottish Government should fulfil its statutory commitment to revising the Strategy by December 2026. We previously made a recommendation for an interim update to the Strategy, as well as bringing forward the revised Strategy date to May 2026. We stand by this advice but given that no interim update has happened, we would reiterate the statutory requirement for the Strategy to be reviewed by December 2026 and Scottish Ministers’ previous commitment[8] to the Panel. We also note that the Periodic Report makes no reference to revising the Strategy.

It is the Panel’s view that since the Act and the statutory fuel poverty targets which it brought in were established under a broadly similar devolution framework to that which exists now, the resulting Strategy and targets should have been developed in full cognisance of reserved and devolved powers. This should have been supported by a strong evidence base that the targets were obtainable based on Scottish Government action. As such, it is the Panel’s view that it is difficult to use the scope of reserved powers to explain missing the targets. Any revised fuel poverty strategy developed should reflect the current view of devolved and reserved powers.

In Scotland, a household is in fuel poverty once it has paid for its housing if a) it needs more than 10% of its remaining income to pay for its energy needs, and b) if after paying for its energy the household is left in poverty (as defined by the Minimum Income Standard).There is no standardised fuel poverty definition across the UK and the Scottish definition, based on the energy costs as 10% of a net income ratio, is recognised as a competent technical and comprehensive definition of fuel poverty giving an accurate depiction of levels of fuel poverty. The definition is critical not only as the measure by which fuel poverty levels are assessed but also as the underpin for any strategy to tackle fuel poverty.

One of the identified shortcomings[9] of the Strategy is that it does not discuss the relative impact of each of the fuel poverty drivers on fuel poverty in Scotland. The Periodic Report does recognise the significance of higher energy costs on fuel poverty levels but not its relative impact. It also does not provide any assessment of the impact of the different actions set out in the Strategy on fuel poverty levels as measured by the Scottish definition, or the lived experience of fuel poverty, modelled or otherwise. This makes it challenging to understand which drivers the Scottish Government considers most pressing to address and which actions are working, or not.

There is also a strategic question about how Scottish Government’s other statutory targets for child poverty, climate change and heat network development connect to the delivery of the fuel poverty targets given the intersectionality that exists between these policy areas. The Panel notes that the Periodic Report makes no assessment of the relationship between the 2030 child poverty target, 2045 climate change target, the 2030 heat network target and the fuel poverty targets. This not only highlights a weakness in reporting but potentially in the management of pan-government strategic programmes.

When the Strategy was agreed, it was the Scottish Government’s plan to have a monitoring and evaluation framework in place before the Periodic Report was produced. The failure to develop an appropriate monitoring and evaluation framework makes the efficacy of actions and progress hard to assess. It also makes it extremely challenging for the Panel to objectively assess the policy and funding impacts set out in the Periodic Report and to fulfil our statutory role of scrutinising the Scottish Government’s progress towards delivering Scotland’s fuel poverty targets and the extent to which the four drivers of fuel poverty are being addressed.

In the Panel’s view the Strategy and Periodic Report fail to develop the links between the definition, targets, drivers and actions. The lack of clear accountability or responsibility for delivery and monitoring and evaluation of the Strategy, insufficient assessment of weighting and prioritisation of the drivers and actions, and a lack of assessment of the impact of the actions on fuel poverty levels, undermines the Strategy and therefore the Periodic Report.

The Fuel Poverty Drivers (Periodic Report pp. 11-30)

Driver 1: Poor Energy Efficiency of the Home (pp. 11-30)

Energy efficiency is an important factor in determining how much energy is consumed in the home. Improving the energy efficiency of Scotland’s homes and buildings is regarded by the Scottish Government as essential to securing a just transition to net zero and ensuring that poor energy efficiency is removed as a driver of fuel poverty. The Heat in Buildings Strategy was published in October 2021, setting out a programme to transform Scotland’s homes and workplaces so that they are warmer, greener and more energy efficient. This included fulfilling the requirement under the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 to report annually on progress against this strategy. The Panel considers that poor energy efficiency of the home is the fuel poverty driver where the Scottish Government has most significant legislative[10], fiscal[11], and policy levers[12] to effect change.

The Panel acknowledges that the funding commitments the Scottish Government has made to energy efficiency programmes are significant. Between the financial years 2021-22 and 2024-2025, this includes a £501 million spend on Area Based Schemes and Warmer Homes Scotland. A further £66.05 million was spent via the Social Housing Net Zero Fund and Home Energy Scotland between the financial years 2021-2022 and 2023-2024[13]. This is part of Scottish Government’s £1.8 billion commitment during this parliament to support delivery of its Heat in Buildings Strategy. However, given the fact that only £790 million[14] has been spent as at the end of Q1 2025/26 and the existence of supply chain challenges in delivering retrofit, the Panel’s view is that Scottish Government may struggle to spend these funds ahead of the end of this Parliament in 2026. It is also noted from stakeholder feedback to the Panel that the funding allocated for energy efficiency schemes has been reduced in real terms.

Although the Panel recognises progress made in developing energy efficiency legislation, the Panel notes that, since the publication of the Periodic Review, the Scottish Government has announced a delay to the Heat in Buildings Bill to ensure that the drafting legislation simultaneously leads to a reduction in carbon emissions and tackles fuel poverty. This alignment is welcome and responds to the Panel’s (amongst others) view of the crucial importance of ensuring that fuel poverty mitigations and considerations are grounded in the Bill from the outset. The delay should not be allowed to slow progress on fuel poverty action.

In the Periodic Report (pg. 11), the Scottish Government states that continued long-term improvements to the energy efficiency of Scotland’s housing stock are being made, with 56% of homes rated EPC band C or above in 2023 – an increase of around 3% from 2022, helping to improve the warmth of homes and reduce energy costs[15]. However, fundamental gaps in the periodic reporting include no assessment of the impact of the investment on tackling fuel poverty and no assessment of whether the rate of energy improvement measures is sufficient to achieve the statutory targets. Consequently, there is no awareness of the rate at which delivery needs to be accelerated to meet the targets. Without an operationalised monitoring and evaluation framework, the Panel is unable to determine the impact on fuel poverty rates from the improvements in energy efficiency interventions.

There is limited data on which measures have been installed and for whom, with few insights into the lived experience of those in fuel poverty once measures have been installed. This makes it challenging to understand whether such measures are having the desired effect or are moving the dial on fuel poverty rates. This is important because we have heard from stakeholders the risks of, for example, some new net-zero technologies and systems not being used in an optimum way post-installation, and particularly after any change in ownership or occupancy.

The Panel has identified that there are opportunities to strengthen data presented in the Periodic Report, the connections between policy actions and fuel poverty outcomes and through these, the potential for targeted impact. Specific examples of where we consider improvements could be made are as follows:

- Information on the rate at which the housing stock below EPC Band C is being improved. Presenting the EPC figures as a percentage of total stock ( pg11) does not enable a distinction to be made between retrofit of existing housing, new build housing, and old homes being removed from the system. This in turn masks the rate of improvement, or otherwise, needed in the existing housing stock including the level of ambient movement that will occur anyway over the period of the Strategy.

- The relationship between the number of households supported by each programme and the improvements in annual EPC with the aggregate data on the number of fuel poor households reached by this, or the overall impact on fuel poverty rates.

- Clarity on how bill savings of £400 are calculated and how this differs from statements made over the last 6 months[16], where bill savings from energy efficiency measures have been estimated as £300 and £500.

- Clarity on the distinction between modelled and measured assessments for energy efficiency measures and the relationship of the outputs from the various programmes with the data in the Scottish House Condition Survey.

- Follow on engagement with those receiving measures to understand the impact on their experience and overall costs.

The Panel recognises that to deliver the Strategy, a stakeholder delivery framework has been developed involving local authorities, agencies and funding programmes. Stakeholders have made representations to the Panel highlighting the risk that local authorities feel under resourced to deliver their Local Heat and Energy Efficiency Strategies. The Panel has also highlighted to the Scottish Government its concerns about the approach to funding Warmer Homes Scotland by amending eligibility criteria with the purpose of aligning demand to available budgets. The Panel is of the view that this is not an appropriate mechanism to manage or understand demand for improving energy efficiency and has recommended that the Scottish Government should not be aiming to restrict demand. It is also essential that the current drivers of underspend[17] on the current Area Based Schemes are understood so these can be addressed in any evolution and prioritisation of the Strategy.

The Periodic Report does not detail the extent of the current Energy Company Obligation programme’s (ECO) and the Great British Insulation Scheme’s (GBIS) (UK Government and Ofgem administered schemes) net effect on the attainment of the Scotland’s fuel poverty targets. Data is provided outlining money spent on programmes administered by Scottish Government, yet these UK-wide initiatives also have implications for fuel poverty programmes. Given the unique challenges faced by many in Scotland, there is a need to understand how supplier and UK Government-administered schemes are impacting the Scottish picture – and where changes may be required in the interests of consumers in Scotland. This should be reflected in the Strategy’s monitoring and evaluation framework. There should be a clear plan with actions to ensure that Scottish consumers benefit proportionally from ECO4, GBIS and other similar measures. The Panel would note that by referencing ECO and GBIS funding under the high prices driver (pg. 24) under “Engagement on Reserved Policy”, the Periodic Report risks conflating reserved energy policy with energy pricing.

The Panel also notes that whilst the Community and Renewable Energy Scheme and Carbon Neutral Islands Project represents important policy action it is unclear what fuel poverty benefits these will deliver.

Overall, whilst funding for energy efficiency is significant and the related policy actions broadly sound, the Panel finds that the outcomes are not clearly defined at the outset and there is a lack of data to show how they are contributing to meeting the fuel poverty targets. This makes it hard to assess their efficacy in relation to fuel poverty. Greater clarity is also needed in reporting the relationship of energy savings to improvements with a clear explanation of the calculation metric and then consistency in presentation of the data. This will increase the potential for impact and targeting of policy actions.

The Panel is of the opinion that the rate at which the energy efficiency of the stock is improved needs to be significantly accelerated to meet the statutory targets. The Panel references in Part 3 that the potential for the current delivery model based around Local Heat and Energy Efficiency Strategies, Warmer Homes Scotland, Area Based Funding and Home Energy Scotland to deliver the step change required is fully evaluated.

Driver 2: Low Household Income (pp. 16-21)

Low incomes make paying for energy challenging, and often impossible, particularly in an era of high energy prices[18]. Fuel poverty is an intersectional issue where multiple coalescing points of vulnerability determine a household’s risk of fuel poverty. We know that those with low incomes often have higher energy needs, including those with disabilities, chronic health conditions, the very young and older people. We also know that low incomes cause people to ration fuel and for some, to self-disconnect their energy supply altogether – both of which impact their health, wellbeing and overall quality of life. Fuel rationing and disconnection also have wider negative impacts, particularly where households are experiencing child poverty and/or more than one person has health issues. Energy debt is a consequence of fuel poverty and the level of energy indebtedness that households find themselves in highlights the unaffordable steps that many take to mitigate fuel poverty personally. Individual actions and behaviours to manage the impact of fuel poverty have knock on implications for the demand on advice and support services.

The Periodic Report highlights the significant spend in providing financial support to individual households to address fuel poverty through winter heating benefits, access to crisis funding and intervention on housing costs. The Panel notes the challenge of reporting on the relationship between financial support and fuel poverty outcomes and therefore, to what extent programmes are effective in reducing fuel poverty long-term and contributing to the fuel poverty targets

In July 2024, Winter Fuel Payment eligibility criteria were changed by the UK Government[19], which resulted in a reduction in the block grant allocation for this policy. We see no evidence in the Periodic Report of an impact assessment of this reduction in income support. The Periodic Report discusses the Pension Age Winter Heating Payment (PAWHP) (the successor of the Winter Fuel Payment). We see no assessment of the targeting of PAWHP or analysis of seasonal energy costs to underpin the level of financial support required. Our evidence from investigations into remote and rural fuel poverty suggests that this is critical.

The Fuel Insecurity Fund (FIF) played a key role in mitigating some of the impacts of fuel poverty and extreme fuel poverty at the peak of the energy price crisis until the closure of the fund in March 2024. If the Scottish Welfare Fund and Islands Cost Crisis Emergency Fund discussed in the Periodic Report are playing a role in replacing the support previously available through the FIF, there should be data available on the level of energy support payments made and the outcomes achieved. The impact of the transition between a direct fuel poverty support fund and a more generic household support fund on fuel poverty mitigation and alleviation should also be made clear.

The Periodic Report refers to several housing interventions – discretionary housing grants, capital investment programmes and rent policies – which can potentially impact on housing costs but again makes no reference to outcomes achieved in reducing fuel poverty.

The Periodic Report does not recognise that under the Scottish Government definition of fuel poverty, and evidenced by Scottish Government analysis, financial support to reduce energy bills has a more significant impact in tackling fuel poverty than interventions that increase income – this is not reflected in policy. In addition, the Panel has raised its concern on the inclusion in the Strategy of policy interventions which relate to wider cost of living challenges. For example, in the Periodic Report there are references to cost-of-living interventions such as free bus passes and free school meals. These do not impact net income as set out in the fuel poverty definition, nor are they considered by the Scottish House Condition Survey in reporting on levels of fuel poverty.

The Periodic Report recognises that although fuel poverty is correlated to low income, it is not equivalent to income poverty. Scottish Government statistics reveal that 31% of those in fuel poverty are not income poor[20]. The Panel therefore seeks acknowledgement that supporting the fuel poor through income-based measures (as often assessed through income-related benefits) risks missing those not in income poverty but in fuel poverty.

The Periodic Report makes a clear albeit high level link between fuel and child poverty. The intersectionality between fuel poverty and child poverty is clear, families are one of the household types more likely to be in fuel poverty[21]. However, this overlap needs to be recognised at a strategy and policy delivery level with programmes developed that speak to both.

Overall, there is significant Scottish Government financial support to increase the income of low-income households, with some interventions directly related to annual assistance with energy costs. However, the Panel questions the relationship between some of the interventions set out in the Periodic Report and addressing fuel poverty and once again, finds that outcomes are not clearly defined at the outset and that there is a lack of data to show how they are contributing to meeting the fuel poverty targets. This makes it hard to assess their efficacy.

Driver 3: High Energy Prices (pp. 22-27)

The Panel recognises that since the Strategy was published, high energy prices have been the primary driver of the increased levels of fuel poverty in Scotland. In spite of recent reductions in energy prices under the energy price cap (which at its peak was £2,380 under the Energy Price Guarantee from October 2022 to June 2023[22]), the average bill paid by mains gas and electricity customers remains high. The October to December energy price cap for 2025 is £1,755 – 44% higher than winter 21/22 [23]. The energy price cap does not protect those customers who rely on unregulated fuels, including oil.

The energy price crisis has left a legacy of huge consumer energy debt, with many households still struggling to pay their energy bills. Intelligence suggests that energy prices will continue to be high until the late 2030s[24] [25]. Scotland’s ambition to eradicate fuel poverty by 2040 will therefore take place in the context of continuing high energy prices.

The Panel’s view is that the current Strategy, and hence periodic reporting, is weakened by the failure to consider the potential impact of each of the fuel poverty drivers on achieving the fuel poverty target and specifically the failure to make clear any assumptions on long-term energy price stability and to evaluate associated risks.

Scottish Government modelling set out in the Periodic Report of what fuel poverty rates would be if energy prices were the same as in 2019 posits both the negative impact of energy pricing, and the positive gains made through actions on other fuel poverty drivers (e.g., income, energy efficiency). These dynamics reinforce our view of the importance of evidencing the relative impact of each fuel poverty driver. The Panel’s view is that high energy prices should be a key area of policy focus but that whilst positive and tangible work on a flexible energy discount mechanism (a social tariff in the language of the Periodic Report) is apparent, the impact of other Scottish Government positions and actions on high prices are less well stated.

Energy markets and regulation are critical to energy prices as a driver of fuel poverty, and the net zero transition of the energy system in Scotland and across the UK will have implications for future energy prices, as the Periodic Report recognises. There is little in the Periodic Report, however, to set out how the Scottish Government expects UK and GB-wide energy policy, pricing and market reform to impact fuel poverty levels in Scotland. Here, the monitoring and evaluation framework could draw out the impact of UK Government policy on Scottish consumers.

The delayed Energy Strategy and Just Transition Plan (ESJTP) (pg. 57), for example, has the potential to significantly impact future energy prices through shifting Scotland’s energy technology mix towards lower-cost, lower-carbon sources of generation and storage. Other energy transition initiatives, such as the Strategic Spatial Energy Plan (which sits with the National Energy System Operator (NESO) with representation from national and devolved governments) are also referenced in the Periodic Report. However, there is no clear assessment of the expected links to fuel poverty or Scottish Government’s approach to influencing towards fuel poverty outcomes.

The UK Government has published its Clean Power 2030 Action Plan, which will impact the final ESJTP and includes some scenario-based modelling of transition timelines and costs by the NESO, which will impact Scotland’s energy transition and costs paid via consumer bills. The links between these policies and the fuel poverty strategy and delivery need to be set out.

Overall, the Panel is conscious of the critical role played by high energy prices in fuel poverty outcomes and that many related levers are not in the Scottish Government’s power. However, the Scottish Government does have capacity to influence as well as its devolved powers. It is the Panel’s view that the Scottish Government should position its fuel poverty strategy and actions in this context and that of ongoing change, accompanied by dedicated evidence and advocacy positions. The material included in the Periodic Report does not permit a full evaluation of progress for this driver.

Driver 4: How Energy is used in the home (pp. 28-32)

How energy is used in the home can and does lead to increased fuel poverty. A lack of understanding of home heating systems, for instance, can cause people to limit their heating use to unhealthy levels[26]. Some people may be signed up to inappropriate or unaffordable tariffs, leading them to unwittingly pay more than they should and potentially to ration their energy use. These challenges are compounded by suppliers not understanding the individual needs of consumers, and recent evidence of supplier malpractice in dealing with people in vulnerable situations[27].

Scotland is the only UK nation to recognise this driver in relation to national fuel poverty programmes. The Panel’s view is that this driver is the least well understood and least well actioned. As the Periodic Report fails to set out a coherent approach to addressing this driver, our reflections on it are limited. The Panel questions how the Warm Homes Discount and Local Heat and Energy Efficiency Strategies listed under this driver in the Periodic Report (but not in the Fuel Poverty Strategy) reflect behavioural interventions. This observation informs our recommendations in Part 3.

This behaviour-related section of the Periodic Report extensively references energy advice, both in terms of Scottish Government services and wider advice offerings. Whilst this advice may influence how energy is used in the home, the mechanism for this is not well stated. Moreover, it is unclear how the fuel poverty impact of advice services is assessed. It would be beneficial, for instance, to understand the impact on the attainment of the fuel poverty targets of the 60,000 annual households in fuel poverty who have benefitted from energy efficiency advice via Home Energy Scotland.

The Periodic Report (p. 84) references the Panel’s early recommendation to review the design of energy advice services to take account of national and local needs, recognising the increased demand for energy advice services since the energy price and cost of living crisis, as well as to review the design of energy advice services, including the funding model. The focus of our recommendation was third sector energy advice services. The Panel’s view is that by focussing on Scottish Government core-funded and UK levy-funded energy and financial advice services there is a lack of recognition of the crucial role that the wider third sector plays, locally and nationally, in mitigating fuel poverty and the funding challenges these advice services face. It also means that the Periodic Report fails to consider advice services holistically. The Periodic Report makes no assessment of the sufficiency and sustainability of the current advice model, and from a customer perspective what works best and where. There is also no evidence in the Periodic Report to draw out the social and economic impacts of these services.

There are key elements of how energy is used and levels of consumption in the home which affect fuel poverty outcomes, including not least self-rationing[28], self-disconnection, the incorrect use of technologies[29], inadequate ventilation or underheating. The role of the Scottish Government in influencing these behaviours should be considered.

The Panel’s key reflection on the driver of how energy is used in the home is that Scottish Government action in this space is not well specified and that where it is listed, the relationship of the driver to behaviours and contribution made to the fuel poverty targets is not clear. It is therefore not possible to assess progress. The Panel would encourage the Scottish Government to reflect on how this behavioural driver is framed, to consider the use of research to better understand the factors that influence how energy is used in the home and through this, the action on this driver’s potential contribution to tackling fuel poverty, and the priority actions that are required to impact on meeting targets.